Weeks #5-#6: Frankenstein Chapters 17-24

Weeks 5 and 6: Frankenstein, chapters 17-24

We are finished with Frankenstein…boo! One of my favorite book studies to date. Next week we move on to George Orwell’s classic dystopian tale…Animal Farm. What happens when a bunch of pigs launch a rebellion? Hmm…gee, I wouldn’t know….

William Wordsworth’s “Tintern Abbey”

In Week #5 we read and discussed a small passage from “Tintern Abbey” (also included by Mary Shelley in chapter 18 of Frankenstein)—probably the most famous poem by one of the most famous British Romantic poets. The Romantic period wasn’t so named because the poets wrote a lot about love, but because they were interested in Nature, Beauty, and Truth (please note the caps!). In 1798, Wordsworth published Lyrical Ballads with his friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Coleridge only contributed a few poems to the volume (including “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”). The Lyrical Ballads weren’t just revolutionary in terms of the language they used (for the common man); they also changed the whole idea of what poetry could and should be about. Instead of writing about kings, queens, dukes, and historical or mythological subjects, Wordsworth and Coleridge wrote most of the poems in Lyrical Ballads about common people, like shepherds and farmers. “Tintern Abbey” is a little bit different in that it’s about the poet himself, rather than a shepherd, but it is still representative of a lot of the changes Wordsworth wanted to make to the way poetry was written. It’s written about common things (enjoying nature during a walk around a ruined abbey with his sister), and it uses a very conversational style with relatively simple vocabulary. It also introduces the idea that Nature can influence, sustain, and heal the mind of the poet. Before William Wordsworth wrote “Tintern Abbey” and the rest of the Lyrical Ballads, literature, and especially poetry, was written pretty exclusively for and about rich people. Wordsworth’s mission was to open up literature and to make it more accessible and enjoyable to normal, everyday people. “Tintern Abbey” is about the ways that we change over time, and the ways that we try to figure out just when and how and why we’ve changed. In short, it’s about trying to square the person you used to be with the person you’ve become.

What’s the Big Diff? 1818 vs. 1831 (Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus)

In Week #6 we briefly discussed some of the main differences between the original 1818 edition and the 1831 edition (which we read). By 1831, Mary Shelley was no starry-eyed 18 year-old and had lost her husband, Percy, and two of her children. In the 1831 text, the tone is grimmer and nature is a destructive machine; Victor is a victim of fate, not free will. She made so many changes, in fact, that there’s a real question about which version we should be reading. I went with the 1831 edition, because, well, that’s the one most people read. Lately, many academic circles believe the 1818 edition is more “pure” to Shelley’s original intent. However, I noted that Percy Shelley may have exercised a heavy-editing hand in the 1818 version, and perhaps Mary felt it was time to make the story completely her own. The 1831 text is differently structured: after Letters 1-4, the chapters are through-numbered, from 1 to 24; this to a large extent obscures the original division into three volumes. Mary Shelley removed many of the references to new scientific ideas, thus detaching the novel from its original intellectual context and the issues that were being debated both publicly and in the Byron-Shelley circle. Frankenstein’s character is very differently conceived: whereas in the 1818 version there are many points at which he could exercise free will and choose not to carry on with his experiments, in the 1831 text he is seen as being, like all human beings, entirely at the mercy of fate, helpless to counteract the forces of chance that appear to control the universe.

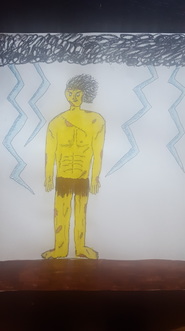

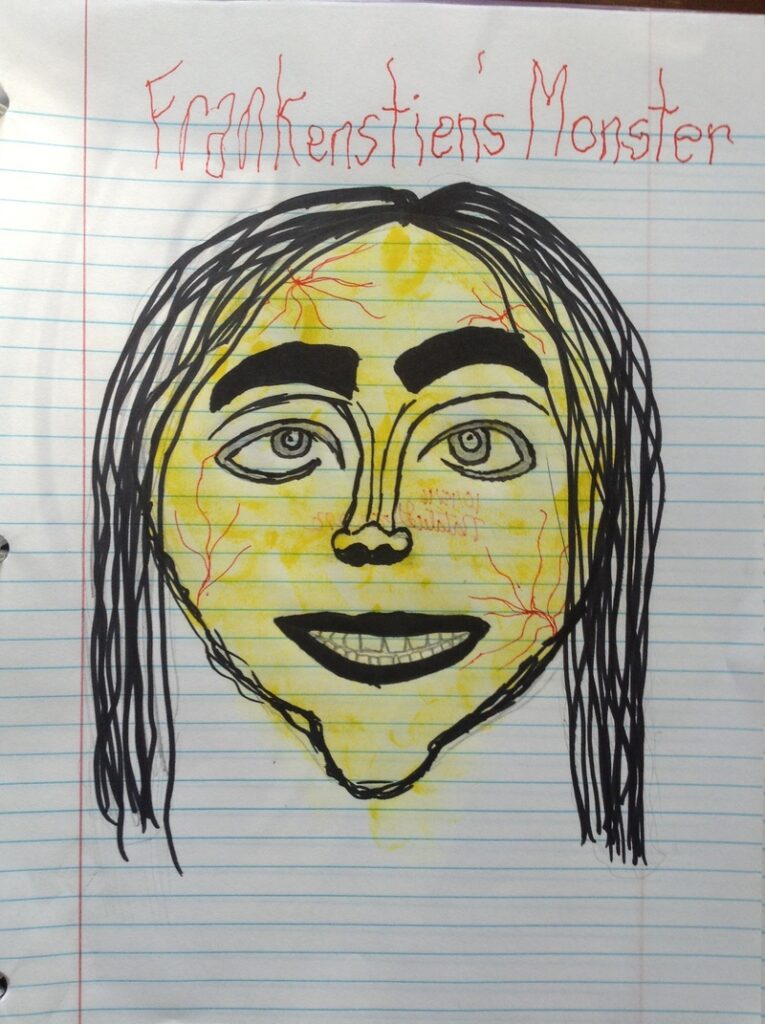

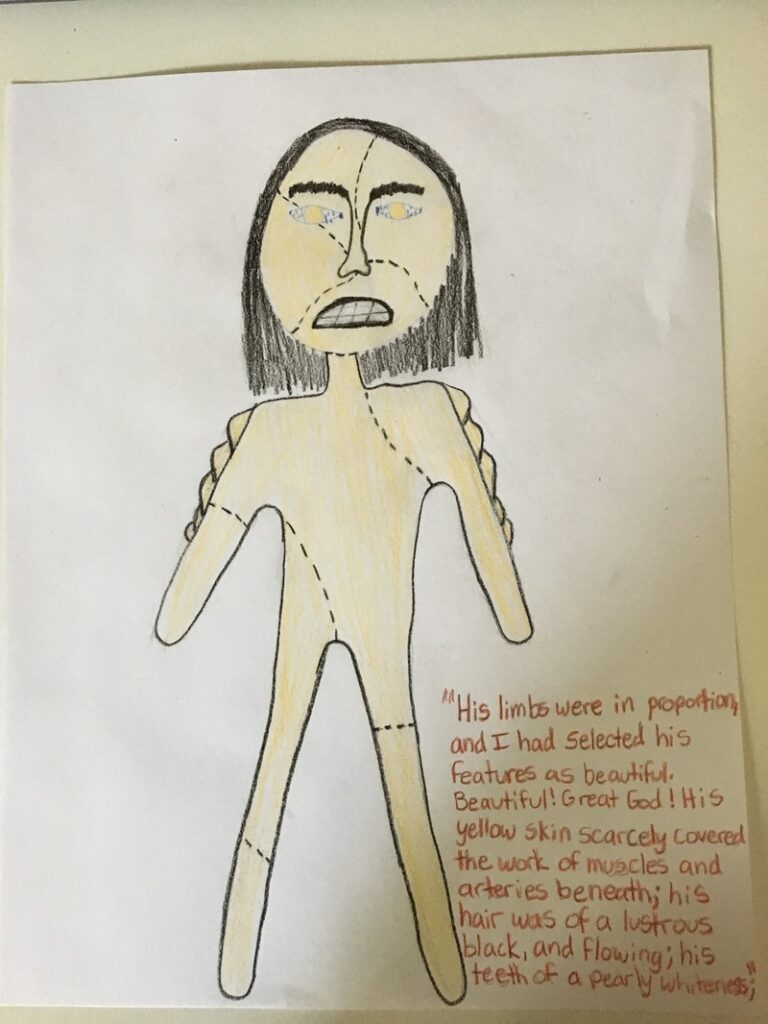

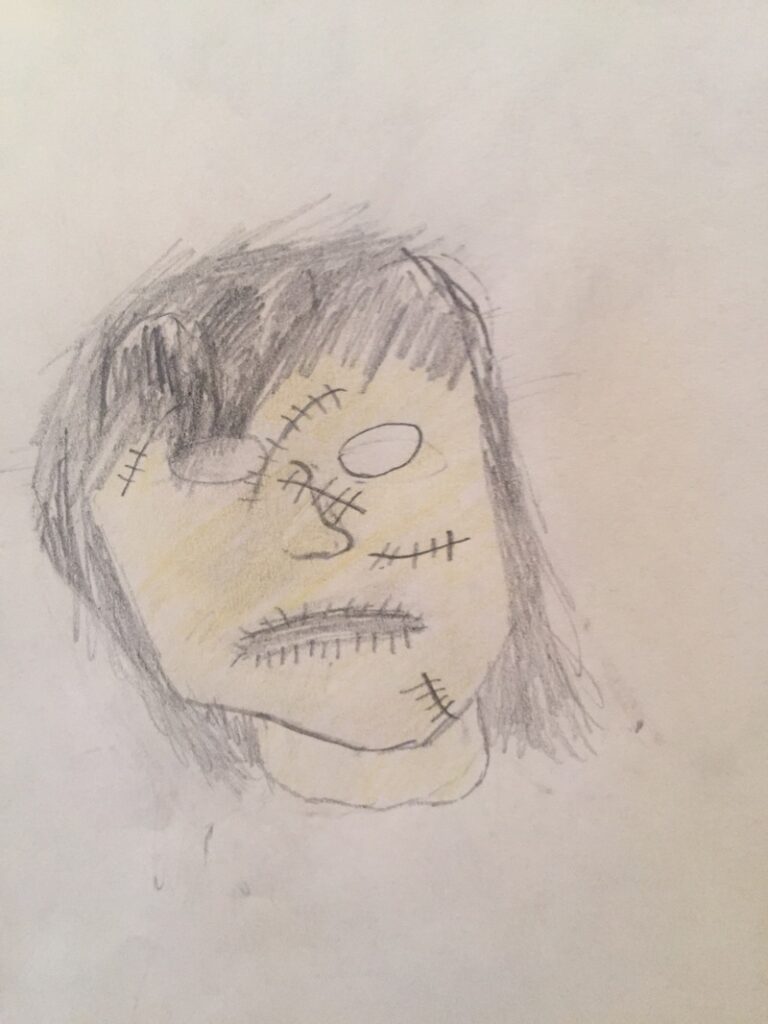

Frankenstein in the Movies and Monster Reveal

We closed our final class on Frankenstein with a quick look at both the classic Boris Karloff 1931 black and white film, and the more recent (1994) film directed by Kenneth Branagh starring Robert DeNiro. In the 1931 film, the creature is depicted as having a huge, square skull and pale corpse-like skin; he is gentle and childlike. In the more recent adaptation, makeup artists researched surgery, skin disorders, and embalming techniques from the early 1800’s. The result was a gray, scarred, hulking, patchwork sort of man. After a discussion about Doppelgängers (Double Goers) we revealed our OWN interpretations of Mary Shelley’s creature (taken from her description in chapter 5). I share them with you here. Wonderful job everyone!